What is consultation-liaison psychiatry?

Consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatry is a subspecialty within psychiatry that involves the interface between psychiatry and other medical specialties. A C-L psychiatrist may work in the inpatient medical setting, the emergency medical setting, or the outpatient medical setting. In each, the C-L psychiatrist provides direct patient care and/or collaborates with other medical specialists as they care for patients. Training in C-L begins in psychiatry residency, when every resident must complete a C-L rotation. Individuals can then pursue a one-year fellowship in C-L psychiatry and subsequently pursue board-certification in C-L psychiatry through the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN).

If you are interested in psychiatry but want to keep up your knowledge of medicine and surgery, C-L psychiatry may be the career for you. See this presentation from the APA.

How is C-L psychiatry different from psychosomatic medicine?

Whereas C-L psychiatry was the term used to describe the field throughout much of the twentieth century, “psychosomatic medicine” was the officially approved name of the subspecialty when it was first recognized by the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) in 2003. The name of the subspecialty was changed to consultation-liaison psychiatry in 2018 in part to address frequent misunderstanding by other physicians and the public regarding the meaning of the term psychosomatic.

What patient populations do C-L psychiatrists serve?

C-L psychiatrists serve patients of all ages from diverse demographic, cultural, and psychosocial backgrounds with complex medical, surgical, neurologic, and obstetric conditions. C-L psychiatrists frequently work as inpatient consultants with patients and families on general medical and surgical units, care for outpatients in outpatient specialty medical clinics, and provide collaborative and integrated care in partnership with primary care providers and other medical specialties.

The breadth and medical complexity of populations served by C-L requires expertise in managing behavioral syndromes that are directly caused by medical problems, as well as the physical and emotional difficulties that arise in patients coping with life changing illnesses. C-L psychiatrists serve patients across the lifespan, developing expertise in managing delirium and other neurocognitive problems, risk assessment, psychopharmacology, pain, addiction, forensic issues, end-of-life care, and the psychiatric sequelae of medical disorders. C-L psychiatrists advocate for high quality, integrated care and help develop ongoing treatment plans for patients with psychiatric needs at hospital discharge and across outpatient levels of care.

What does the liaison component of consultation-liaison mean?

The liaison component speaks to a C-L psychiatrist’s work providing consultation and education for the patients of teams specializing in organ transplantation, cardiac care, critical care, cancer, burns, women’s health, infectious diseases, neurologic illness, brain injuries, trauma, and many other general medical and surgical problems. As a liaison, the C-L psychiatrist bridges gaps in communication and understanding among patients, clinicians, administrators, and other staff. C-L psychiatrists are often involved in cases with medicolegal, ethical, or system-level implications.

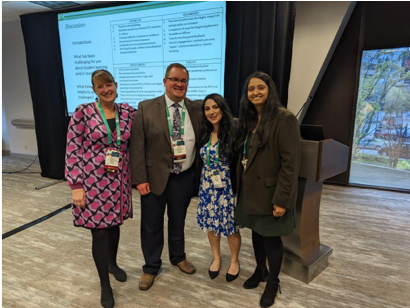

How do I learn more about C-L Psychiatry? What if my medical school doesn’t have C-L electives? (Insert Picture 3)

The first and most straightforward step is through your institution. Find out whether the Department(s) of Psychiatry that your medical school is affiliated with has a Consultation-Liaison Service. Ask to meet with faculty members who are involved in those clinical and academic areas to learn more about the subspecialty.

Some medical school psychiatry clerkships include exposure to C-L psychiatry; some also offer medical student electives in C-L for those who have already completed a clerkship in psychiatry. The best way to find out about such electives is to go to the medical student webpage for any program that you might be interested in or which you are considering for residency to and look for a link to electives for visiting medical students. A list of all U.S. C-L Fellowship programs is located in the Fellowship section of the ACLP website. Many of these programs host electives for medical students through their affiliated medical schools. Please also feel free to contact one of our Medical Student Education Committee members directly for advice or assistance.

Some medical school psychiatry clerkships include exposure to C-L psychiatry; some also offer medical student electives in C-L for those who have already completed a clerkship in psychiatry. The best way to find out about such electives is to go to the medical student webpage for any program that you might be interested in or which you are considering for residency to and look for a link to electives for visiting medical students. A list of all U.S. C-L Fellowship programs is located in the Fellowship section of the ACLP website. Many of these programs host electives for medical students through their affiliated medical schools. Please also feel free to contact one of our Medical Student Education Committee members directly for advice or assistance.

If your institution does not have an active C-L service or Division (or even if it does and you’re curious about experiencing other institutions), consider signing up for an “away elective” in C-L. To find out about electives at institutions other than your own, go to VSLO (see above).

Get involved at the local, regional, national, and international level! Browse the websites for some of the major psychiatric organizations like the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the main C-L organizations such as the Academy of Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry (ACLP) or European Association of Psychosomatic Medicine (EAPM). Look for medical student memberships (often for reduced rates), conferences to attend, awards to apply for, and mentorship programs.

Utilize student-focused organizations. Consider joining PsychSIGN, a national psychiatry interest group with regional chapters, which will give you access to numerous opportunities to learn more about careers in psychiatry, through informal gatherings, activities at larger conferences, networking, and more. Membership is free!

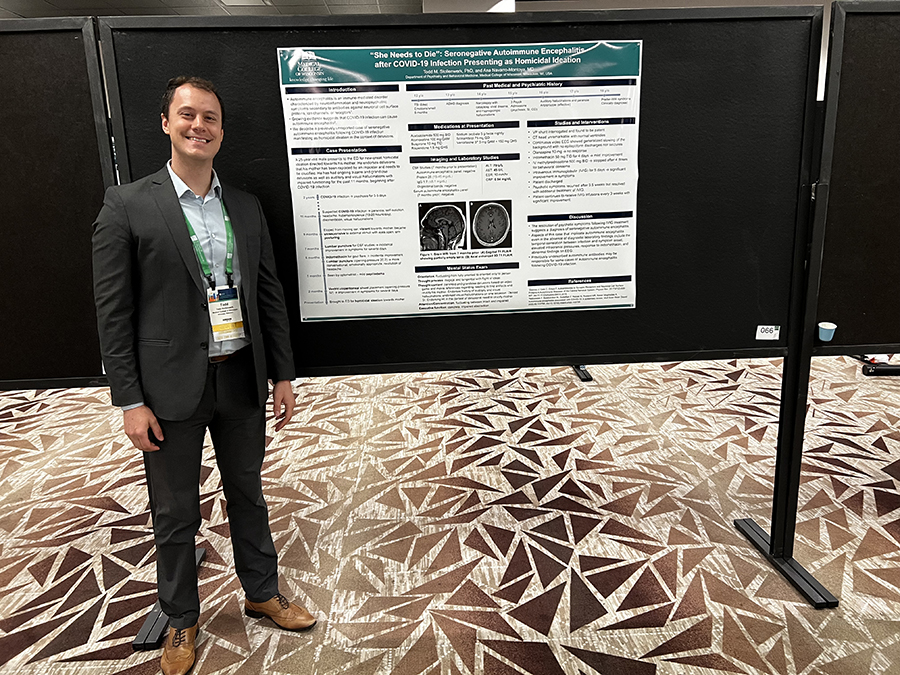

Each year, the ACLP holds a national meeting in November. Students are welcome and encouraged to attend! Information on future and past meetings can be found

Each year, the ACLP holds a national meeting in November. Students are welcome and encouraged to attend! Information on future and past meetings can be found  Some medical school psychiatry clerkships include exposure to C-L psychiatry; some also offer medical student electives in C-L for those who have already completed a clerkship in psychiatry. The best way to find out about such electives is to go to the medical student webpage for any program that you might be interested in or which you are considering for residency to and look for a link to electives for visiting medical students. A list of all U.S. C-L Fellowship programs is located

Some medical school psychiatry clerkships include exposure to C-L psychiatry; some also offer medical student electives in C-L for those who have already completed a clerkship in psychiatry. The best way to find out about such electives is to go to the medical student webpage for any program that you might be interested in or which you are considering for residency to and look for a link to electives for visiting medical students. A list of all U.S. C-L Fellowship programs is located  Hospital administrator:

Hospital administrator: